The Middle East

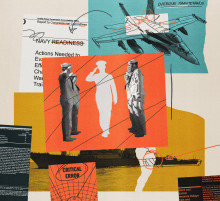

During my thirty-year military career I deployed to the Middle East multiple times. My interest in the region intensified each time, and remains high today.

I always was a bit adrift as to why we were there. And while I would never suggest that Former Governor of Alaska, Sarah Palin, is someone with a deep understanding of the region, I vividly recall something she said while she was a vice-presidential candidate. When asked if the United States should be involved in the region, she said, “Let Allah sort it out.”

Now, over a decade later, veteran U.S. diplomat, Martin Indyk, is raising that same question in a thoughtful way. Here is how he begins his piece, “The Middle East Isn’t Worth It Anymore:”

Last week, despite Donald Trump’s repeated pledge to end American involvement in the Middle East’s conflicts, the U.S. was on the brink of another war in the region, this time with Iran. If Iran’s retaliation for the Trump administration’s targeted killing of Tehran’s top commander, Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, had resulted in the deaths of more Americans, Washington was, as Mr. Trump tweeted, “locked and loaded” for all-out confrontation.

Why does the Middle East always seem to suck the U.S. back in? What is it about this troubled region that leaves Washington perpetually caught between the desire to end U.S. military involvement there and the impulse to embark on yet another Middle East war?

As someone who has devoted four decades of his life to the study and practice of U.S. diplomacy in the Middle East, I have been struck by America’s inability over the past two administrations to resolve this dilemma. Previously, presidents of both parties shared a broad understanding of U.S. interests in the region, including a consensus that those interests were vital to the country—worth putting American lives and resources on the line to forge peace and, when necessary, wage war.

Today, however, with U.S. troops still in harm’s way in Iraq and Afghanistan and tensions high over Iran, Americans remain war-weary. Yet we seem incapable of mustering a consensus or pursuing a consistent policy in the Middle East. And there’s a good reason for that, one that’s been hard for many in the American foreign-policy establishment, including me, to accept: Few vital interests of the U.S. continue to be at stake in the Middle East. The challenge now, both politically and diplomatically, is to draw the necessary conclusions from that stark fact.