Who Brings Us AI?

When someone mentions artificial intelligence – AI – we typically think of some Silicon Valley tech titan dressed in jeans and an ever-so-sheik sport coat.

But as they say, that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Few of us understand how enormous troves of data needed to have AI gets assembled and crunched.

Cade Metz helps us understand the unseen underbelly of the tech industry. It’s a revealing – and troubling – look at the cost of doing business to get that next cool app. Here’s how she begins:

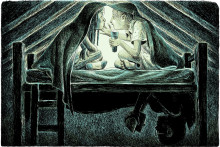

BHUBANESWAR, India — Namita Pradhan sat at a desk in downtown Bhubaneswar, India, about 40 miles from the Bay of Bengal, staring at a video recorded in a hospital on the other side of the world.

The video showed the inside of someone’s colon. Ms. Pradhan was looking for polyps, small growths in the large intestine that could lead to cancer. When she found one — they look a bit like a slimy, angry pimple — she marked it with her computer mouse and keyboard, drawing a digital circle around the tiny bulge.

She was not trained as a doctor, but she was helping to teach an artificial intelligence system that could eventually do the work of a doctor.

Ms. Pradhan was one of dozens of young Indian women and men lined up at desks on the fourth floor of a small office building. They were trained to annotate all kinds of digital images, pinpointing everything from stop signs and pedestrians in street scenes to factories and oil tankers in satellite photos.

A.I., most people in the tech industry would tell you, is the future of their industry, and it is improving fast thanks to something called machine learning. But tech executives rarely discuss the labor-intensive process that goes into its creation. A.I. is learning from humans. Lots and lots of humans.